Apollo Nkwake, Katrina Bledsoe and I are editing a book titled Working with Assumptions to Unravel the Tangle of Complexity, Values, and Cultural Responsiveness (Information Age Publishing). My chapter is (tentatively) titled: Assumptions Through a Complexity Lens. In it I am going to treat assumptions themselves (not the programs they are assumptions about) as complex systems, and work through the implications for Evaluation. Section headings may change, but as of now they are:

- Framing the Discussion – “Complexity” and “Assumptions”

- Sensitive Dependence X Conditional Relationships in Evaluation Models

- Emergence X Causal Chains in Evaluation Models

- Networked or Linear Assumption Order?

- Assumptions with Respect to Emergence, Social Attractors, and Sensitive Dependence

- Assumptions in an Ecological Framework

As part of my research for the chapter, I reread a report I wrote on implicit assumptions. So doing reminded me of several assumptions about models that are all too common in our business. I’m taking this opportunity to publicize them here, in the hope of encouraging people to change their ways. I’ll readily admit that what I advocate is in the “do as I say not what I do” tradition. During most of my career I have ignored or was blind to these issues. I plan to repent. Time will tell.

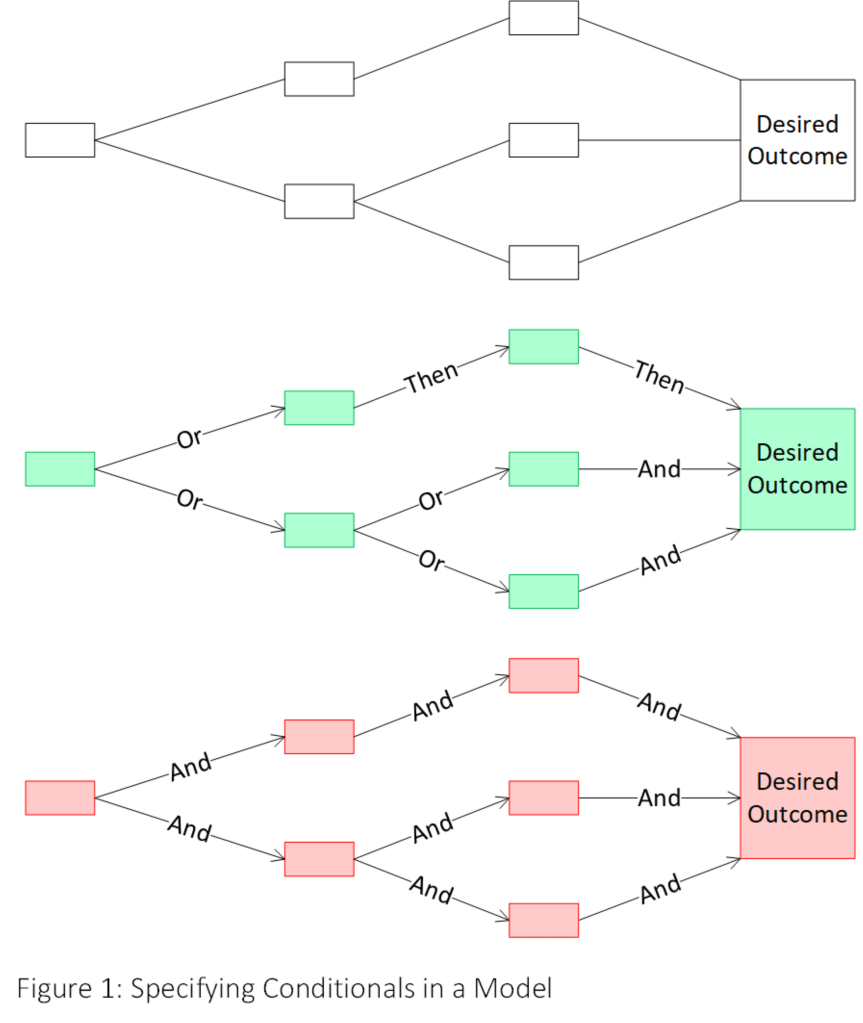

“And/or” and “then” specification

In Figure 1 the model at the top depicts the kind of logic we usually use. The implicit assumption is that all the causal relationships are equally important. I say this because the nature of the connections is not labeled. If we don’t make the differentiation, we must think that doing so does not matter.

The green and red models are architecturally identical to the white one. But unlike what we traditionally do, the colored versions tell radically different stories. The green version shows a program that has a reasonable chance to succeed because there are so many “or” paths, i.e., there are multiple paths to success. Also, paths not labeled “and/or” are labeled “then”, indicating that we have high confidence that if the precursor appears, so too will its successor.

The red version shows a program that is doomed to fail because to achieve the desired outcome, all paths must work. We live in an uncertain world. What are the odds that all our hypotheses about causal relationships are correct?

I have been thinking about this for a long time, but what brought it home for me was my involvement in a DARPA-funded project for modeling ground truth with a novel agent-based modeling methodology.

- Simulation Using Events and Goals – A New Approach to Agent-based Modeling;

- Social Causality with Agents Using Multiple Perspectives — the Movie

Too many “and” relationships froze the model. Why not in real-life too? I don’t think it is always necessary to make and/or distinctions for all relationships in a model, but I do think that the more the better. It concentrates the mind. I also think there may be relationships where we genuinely do not know if a relationship is an “and” or an “or”. That can be enlightening too. I’m all for admitting ignorance.

Confidence in Relationships

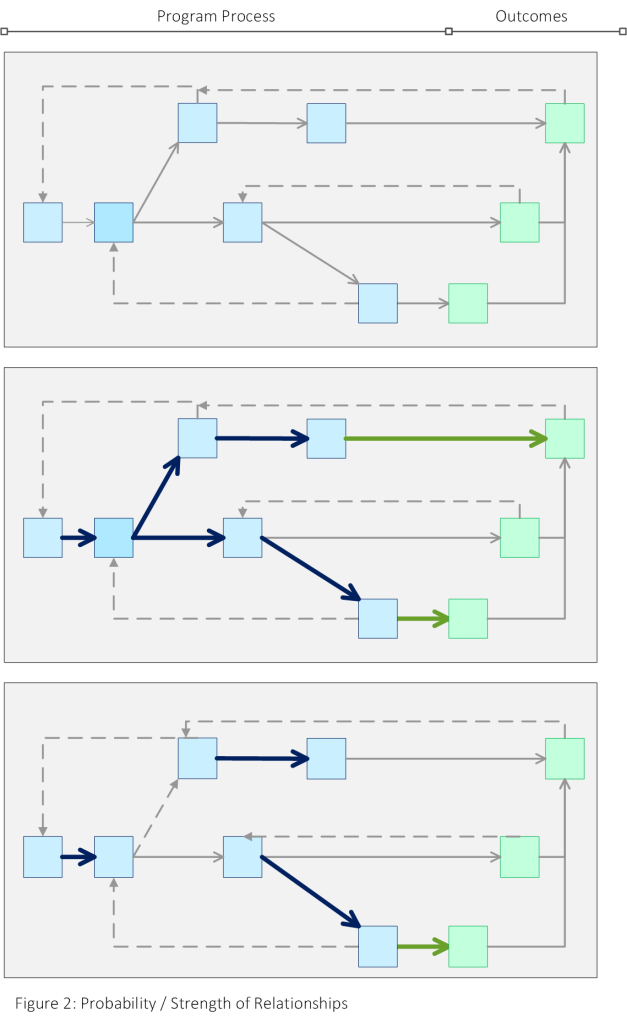

In my experience we are too casual about whether we believe that connections in models will manifest. I think our problem is that we confuse models for explanation and models for program operation and evaluation. If we want to explain how a program should work, all we need to do is to draw the connections. But if we want realistic expectations as to whether the program will succeed, we need to specify whether a connection will manifest itself when we operate the program. As with “and/or” relationships, the fact that we do not make the distinction must mean that we do not care about the distinction. We just assume that models for explanation and models for program operation/evaluation are the same. That can get us into trouble, as illustrated in Figure 2. (To make the visuals clear, “forward” relationships are solid and feedback relationships are dashed.)

The top model is what we usually do – draw undifferentiated connections among program elements, among outcomes, and between program and outcome. The middle model tells a happy story. The model builders are confident that two paths have a good chance of leading to at least one outcome. The bottom model is depressing. There is no high-confidence path that leads all the way through the model.

Strength of Relationships

We can reinterpret the connectors. Instead of signifying confidence in whether the relationship will manifest, they can signal the strength of the relationship. Thick lines would mean that there is a strong causal relationship between the connected elements. Narrow lines would signify a weak connection.

From this point of view, the top panel implies three possible assumptions. 1) We do not care about whether connections are strong or weak. We only care whether they exist. 2) We do not know enough to specify strength for any of the relationships in the model. 3) Specifying connection strength does not add anything of value, so why go to the trouble?

My view is that the strength of a relationship does matter. If a program theory shows too many weak connections, there is not much point in going to the trouble and expense of implementing the program. Or alternatively, if a program theory shows too many weak connections, it might be worthwhile to redesign the program. Looked at this way, the middle panel provides a fair bit of confidence that the program can achieve its goals. There are two paths that show a strong relationship between the initial program, its intermediate activities, and an outcome. The bottom panel does not inspire much confidence.